Before the 1860s, the only way to communicate between Britain and the United States was by mail. Links between the two countries had improved with the development of fast steamships, but considerable delays were still involved. The mid-nineteenth century was, however, the age of the telegraph.

Overland telegraphs in Britain, the US and throughout the world had enabled fast and accurate communication links. Experiments had also shown that cables could be laid underwater: the first submarine telegraph link between Dover and Calais was completed in 1851.

Scientists, engineers and businesses began to consider the possibility of a submarine link across the Atlantic. The distance was daunting: while the Dover-Calais cable was 25 miles long, the easiest route across the Atlantic (between Ireland and Newfoundland) was approximately 1600 miles. Initial surveys were, however, optimistic.

Lieutenant Maury, surveying the ocean bed for the United States Navy, found a plateau “which seems to have been placed there especially for the purpose of holding the wires of a Submarine Telegraph…”.

This initial optimism led to the speedy financing and provision of a cable laying expedition in 1857. Difficulties with the cable and laying techniques led to delays and after the cable was laid it soon failed. An investigation blamed faults in the cable, which was not strong or well-insulated enough for the stresses of cable laying or the conditions on the ocean floor.

It had also been manufactured in three sections and, when they were joined, the twist ran in opposite directions! The problems with the 1858 cable highlighted that submarine cables display different characteristics from land telegraphs. William Thomson, later Lord Kelvin, was brought in as an advisor and developed instruments to overcome the problems.

He found that an undersea cable acts as a long capacitor, storing the electrical pulse and then gradually releasing it, making the signals difficult to read. To sharpen the signals Thomson sent a short reverse pulse immediately after the main pulse. He also invented better sending and receiving instruments.

In 1864 Cyrus Field, with the help of John Pender, a Manchester cotton manufacturer, the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company was formed.

A new cable, mechanically stronger than the previous one, was manufactured within a year. The next expedition set off in 1865. This time, the cable had been carefully tested during manufacture and tests were also carried out on board ship.

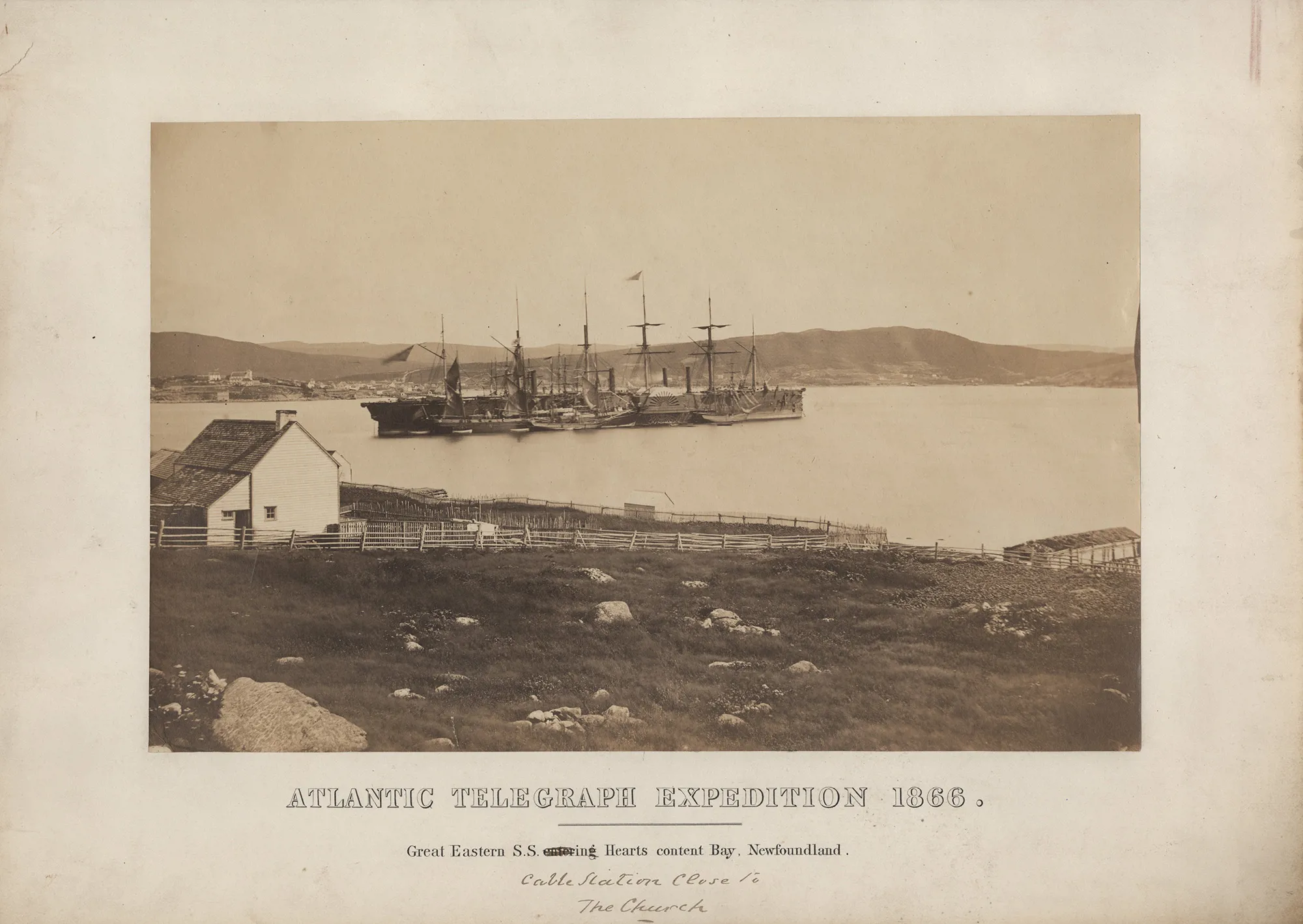

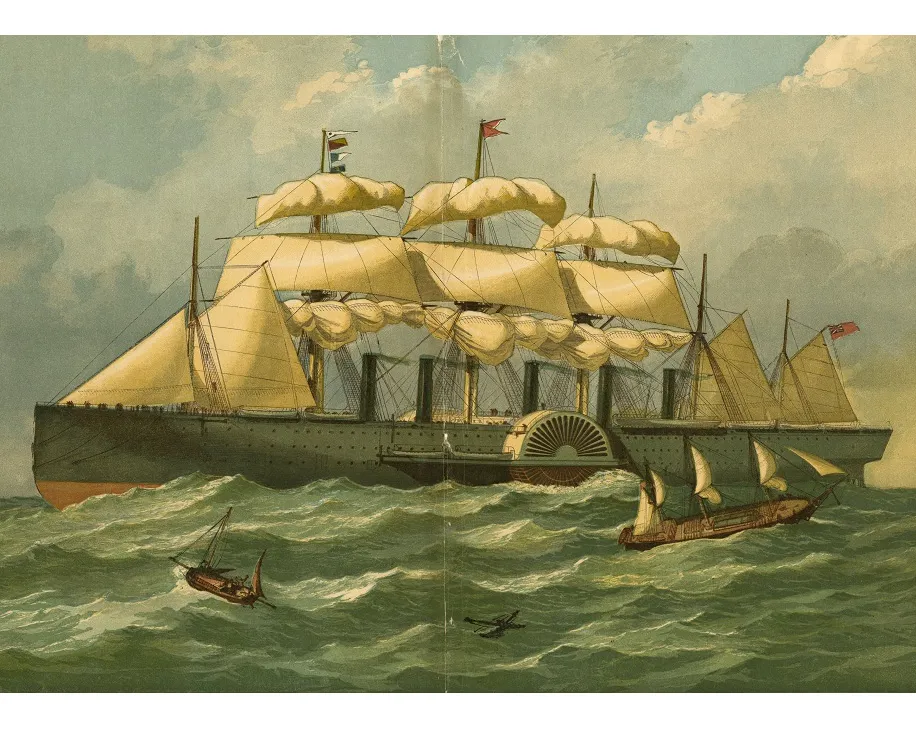

The largest ship afloat, Brunel's SS Great Eastern, was chosen to lay the cable as it was the only vessel with sufficient room for the vast cable drums. After setting off from Ireland on 23 July 1865, tests showed that the cable was passing out smoothly with no effect on the insulation. A few hours later, tests showed a fault in the cable.

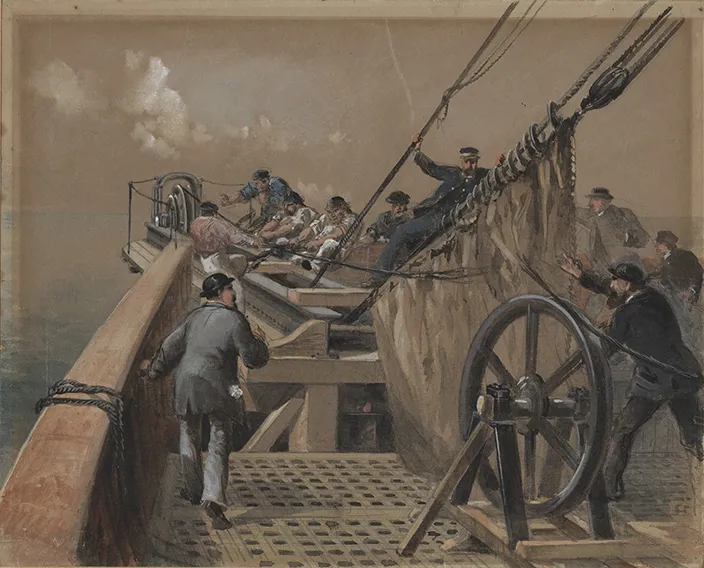

Slowly and carefully, the ship was reversed and the cable gathered back in so that the affected portion could be cut out. Six days later, another fault occurred and was repaired. Two days before the ship reached Newfoundland, another minor fault was discovered and the affected portion was brought back on board for tests. This time, disaster struck. The cable snapped and vanished overboard. Robert Dudley, a member of the expedition, painted the scene showing the moment the cable snapped.

Many attempts were made to grapple for the cable, but the ship was running out of fuel and time. Eventually, they sailed on, having marked the point at which the cable was lost. Despite this calamity, they had proved that the new cable was far more reliable and that the Great Eastern was a successful cable-laying ship.

The cable was finally laid the following year, in 1866. This time the expedition went smoothly. They even managed to retrieve the 1865 cable, laying two cable links across the Atlantic. The Great Eastern sailed into Heart’s Content, Newfoundland, on the 27 July, having successfully linked the two countries across 1600 miles of ocean. In April 1865, news of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln had taken 12 days to reach the British newspapers.

When James Garfield was shot in 1881, it was reported within hours.