Code-breaking during World War II descends from a long and ancient tradition.

Ciphers have been in existence almost as long as writing itself. The ancient Egyptians used them for religious purposes and there are possible references to the use of code in Homer and Herodotus.

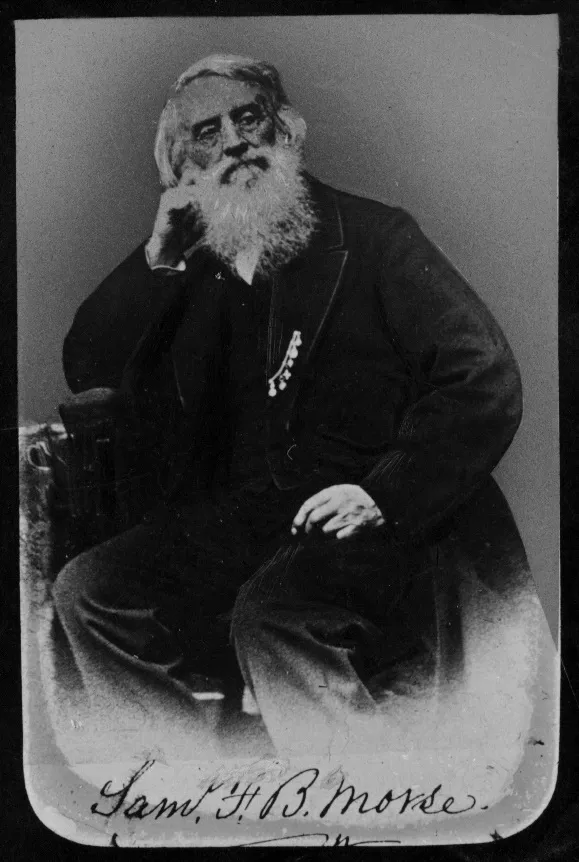

In the nineteenth century, telegraph codes such as those devised by Samuel Morse and Baudot were not intended for secrecy but for ease of transmission and brevity.

Ciphers were intended to render messages secret and came into wide usage with the advent of radio communications.

During World War II some encipherment was still carried out by hand, but for most messages electrical code and cipher machines were used.

The Germans had several including the Enigma machine, the Lorenz SZ40 and the Siemens Geheimschreiber. The British used a Type X machine.

Each machine could be used to produce many different ciphers and all were thought to be secure against unauthorised decipherment. It was difficult but not impossible to break them either by the capture of their instruction books, by human error and carelessness or through an unrecognised weakness in the cipher system itself.

Morse and Wheatstone

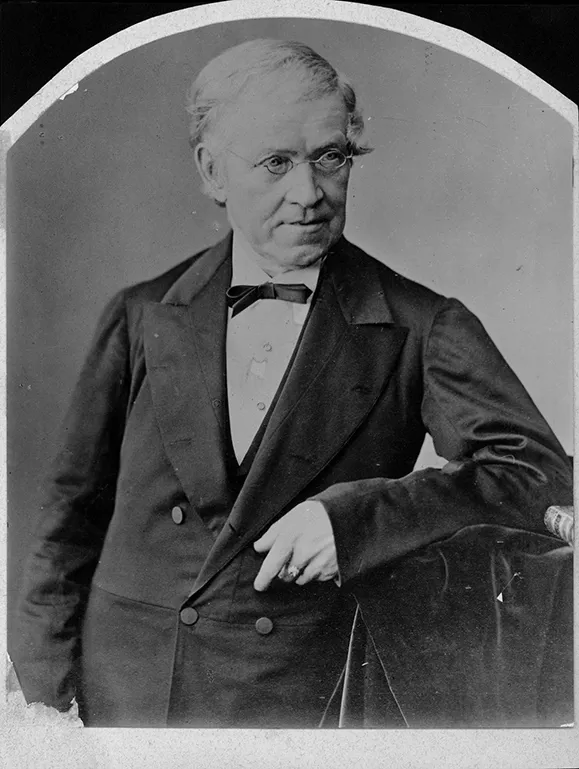

Cryptography became widespread with the invention of the telegraph. Morse code was introduced in 1844 but was not intended to be a secret code so others were developed for this specific purpose. An early example of this was the Playfair cipher developed by Charles Wheatstone ten years later.

Wheatstone’s cipher arose from his work in telegraphy and was designed to keep telegraph messages secret. He also developed rules for its use, which made it difficult to break but also complicated to use.

A friend, Lyon Playfair, 1st Baron Playfair of St Andrews, was given the task of demonstrating it to Government. As a result Wheatstone’s cipher became known as the Playfair cipher. Despite Playfair’s talents as a promoter of science, the Foreign Office deemed it to complex for their staff.

Wheatstone's experiments were precursors of many enciphering machines which were developed during the twentieth century and his cipher was used by the British during the Boer War and World War I.

Samuel Morse

Interestingly, the Germans used a variant of it for hand codes during World War II. It was used extensively for routine unit-to-unit communication by the army, SS and police, while the navy used it for ship-to-ship communications.

The advent of wireless telegraphy (radio) allowed any military or naval unit to be contacted at a distance and instantaneous two-way communication could ensue. However, this traffic could be heard by anyone in possession of a wireless receiver and during wartime, the enemy could monitor the traffic in the safety of their own territory.

World War I served as a catalyst for the development of cipher machines but it was not until after the war that machines were developed to prevent unauthorised eavesdropping.

The application of electricity to coding machines meant that complex procedures could be accomplished quickly. Relay systems were used and electric typewriters were converted for encryption.

Charles Wheatstone

World War II Code-Breakers

In the summer of 1939, with war looming, British cryptanalysts of the Government Code and Cipher School were evacuated to Bletchley Park, a Victorian mansion located about 50 miles from London in Buckinghamshire. It was headed by a naval officer, Commander Edward Travis.

By listening to the ever-increasing German radio traffic, it was estimated that a huge number of people would be required to deal with the material in the decoded intercepts from Enigma and other German ciphers.

Radio operators were taken on at various sites to intercept enemy radio traffic, while Bletchley Park took on WRNS (Women’s Royal Naval Service) personnel to act as decoding clerks, engineers, mathematicians and intelligence experts.

A total of 10 000 people worked at Bletchley, at various locations scattered around Britain and with the Allied armies in the field. The analysed material they dealt with from Enigma, later Axis machines, and German hand ciphers was known as Ultra.

The Bombe

At first, most radio traffic was generated by the Enigma machine. Each of the German services used a different model of it and devised its own codes and procedures. Despite help in the early stages from Polish intelligence agents and the occasional captured code book, it took time to break the ciphers. The principle aid for deciphering Enigma traffic, which Alan Turing helped to develop, was the ‘bombe’.

Alan Turing was an early Bletchley Park recruit. In 1936 he had published a paper, “Computable Numbers”, now recognised as the theoretical basis of the modern computer. In July 1939, as a member of the British delegation that went to Poland, he was given complete details of the Polish bomba. These bombas, machines originally developed in Poland, penetrated the German Enigma ciphers in extensive trials by working at a few characters a second.

Turing worked on a much improved British version - the ‘bombe’ - to which he contributed his considerable knowledge of mathematics and mechanical engineering. The bombe developed by the Bletchley team was an electromagnetic relay machine named the ‘bronze goddess’. It stood eight feet high and had wheels corresponding to the rotors of the Enigma together with other complicated circuits. It was essentially an Enigma machine in reverse, but much more complex.

Colossus

T H (Tommy) Flowers was the chief architect of Colossus, the code-breaking electronic computer used at Bletchley. Flowers joined the Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill in 1930. His major research interest was long-distance signalling, especially in transmitting control signals to replace human telephone operators with automatic switching equipment.

Flower’s Colossus was aimed at the ciphering system generated by the heavy on-line cipher machines originally designed to operate over wires rather than radio, but eventually used for radio transmissions and therefore liable to be overheard and possibly deciphered. The machines most often used by the Germans were the Lorenz SZ40/42 and the Siemens Geheischreiber.

Both were designed to encipher and transmit the message in one operation at the transmitting end. At the receiving end, the pattern of marks and spaces that were produced by a system of cams and gears within the transmitting machine were reversed but this had to be kept in step to the same starting point as the transmitter- which could be any one of millions.

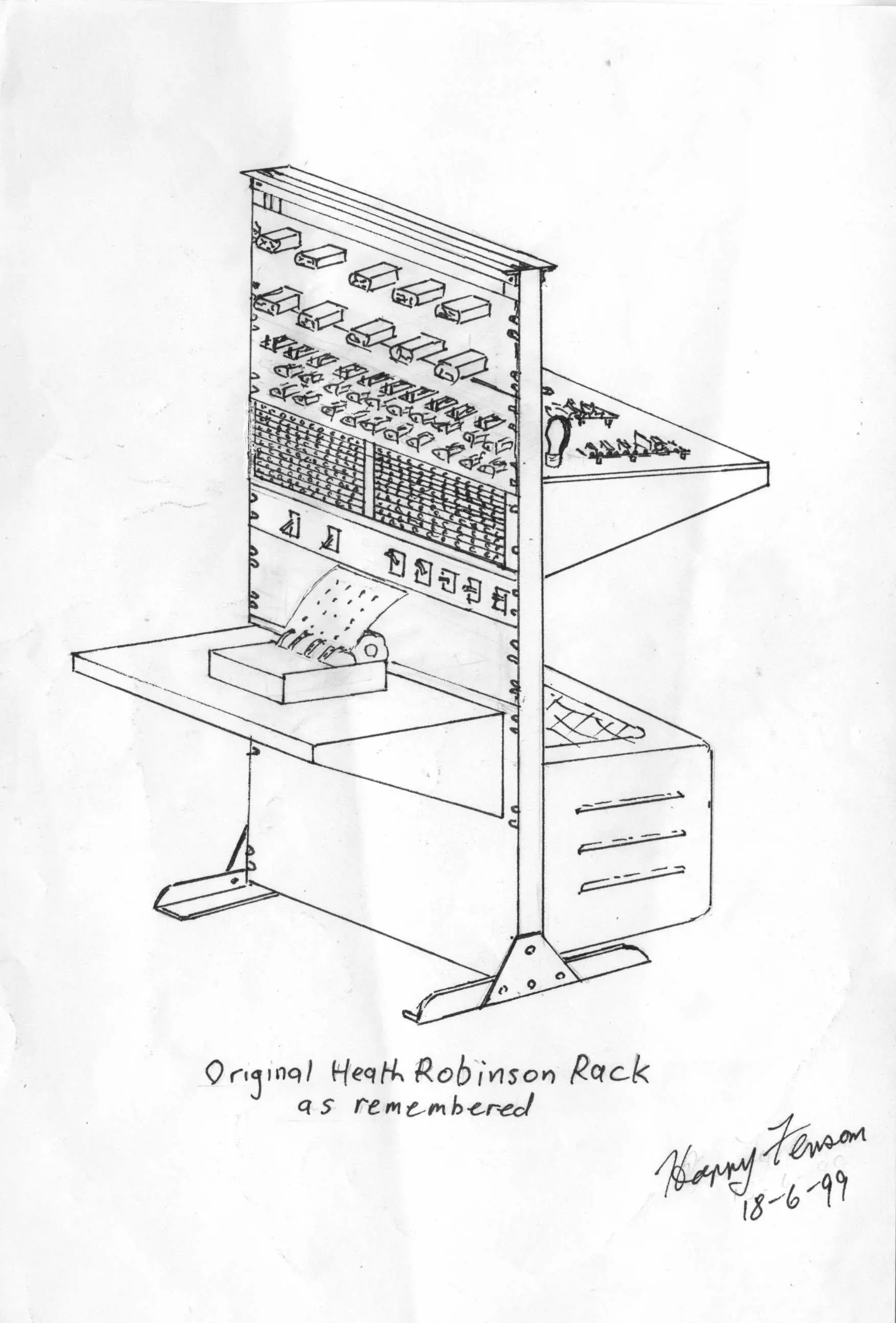

The challenge they had at Bletchley Park was to decipher a system which required the receiving machine to be set so that the pattern of restoration kept in step with the pattern at the transmitting end. Even if they found the pattern, they had to try millions of possibilities before they could break into the cipher. This is what the Colossus, and another machine affectionately dubbed the ‘Heath Robinson’ after the eponymous artist whose cartoons depicted absurd machines, were designed to do.

How code-breaking aided the war effort

Ultra intelligence had an effect on several operations during the war from the invasion of Crete, the campaign against Rommel in North Africa, and, perhaps most important of all, during the D-Day landings. Ultra allowed the Allies to learn that their dummy preparations against Calais had been taken seriously by the Germans and, once the Normandy landings had begun, the Allies knew the location of almost all the German units in the area.

Ultra also gave the British and Americans invaluable intelligence experience, and the wartime cooperation forged between them was continued in the UKUSA Accord under which the United States, Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand agreed to coordinate their intelligence efforts around the world.

In 1999 the IET Archives held an exhibition looking at German encryption during World War II and the beginnings of British computer technology as the men and women of Bletchley Park worked to break the German codes. Exhibits showed the development of cryptology and cryptanalysis from a nineteenth century cryptographic device, through to a range of encryption machines used during World War II.

Copies of the accompanying brochure, full of information and images, are still available and can be obtained from the archives staff, please contact us to request a copy.

We’re upgrading our systems, and this includes changes to our customer and member account log in, MyIET. It’s part of our big picture plan to deliver a great experience for you and our wider engineering community.

Whilst most of our websites remain available for browsing, it will not be possible to log in to purchase products or access services from Thursday, 17 April to Wednesday, 30 April 2025. Our Member Relations team is here to help and for many of our services, including processing payments or orders, we’ll be able to support you over the phone on +44 (0)1438 765678 or email via membership@theiet.org.

We apologise for any inconvenience this may cause and thank you for your understanding.

For further information related to specific products and services, please visit our FAQs webpage.