In 1858, the first telegraph cable was laid across the Atlantic Ocean.

It was both the culmination of years of effort and the first tentative step to a practical, permanent communications link between Britain and the US.

The story of the 1858 cable is one of (possibly unfounded) optimism, a battle through red tape and a rough and ready approach to practical issues that would eventually lead to the failure of the project.

This failure would, however, enable the success of the transatlantic cable to come.

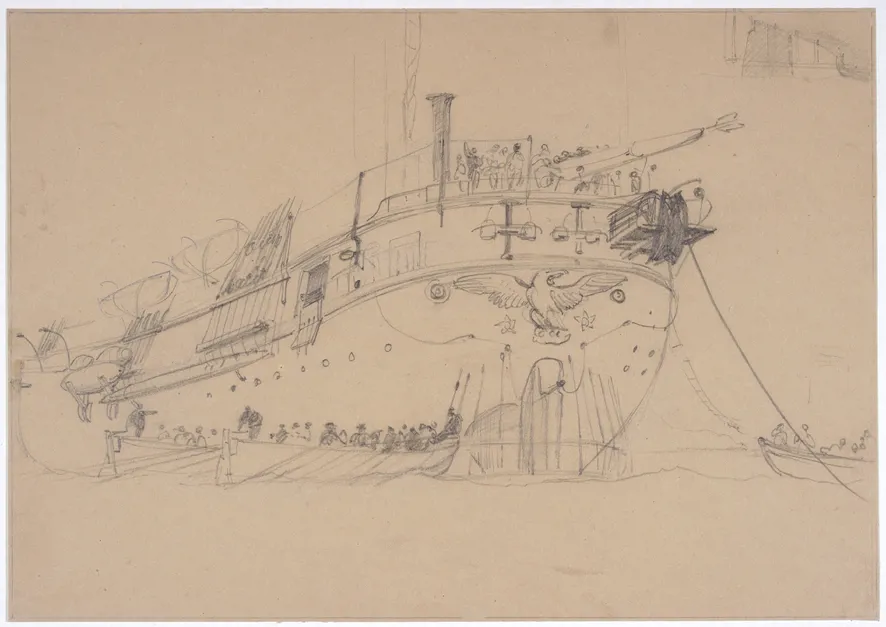

The crew of the Agamemnon

The beginnings

The project had started in the 1840s and 50s with the ambitious vision of a few US and British engineers and businessmen, including Samuel Morse, Frederic Gisborne, Cyrus Field and Charles Tilston Bright.

The overland telegraph network had spread across Britain and America and some submarine cables had already been laid, mostly short cables making as much use as possible of tried and tested overland cable technology.

The problem was that underwater cables were different from those laid overland: there were issues with retardation which were still not fully understood. The longer the cable, the more serious the retardation effects and this was by far the longest cable to be planned. There were also practical manufacturing issues: who would make such a long cable and how could it be laid? What about the problems of laying a cable in deep water?

Practical commercial interests and science determined the cable’s route. Initial soundings indicated that the shortest route was also the best: a plateau between Ireland and Newfoundland. Almost as important were the concessions negotiated with the Newfoundland authorities, which gave the company a monopoly on cables laid in the area for fifty years. Although initial finance for the project had come from the US, by the time the cable came to be laid a great deal of money had come from the British side as well, including a pledge from the British Government.

Laying the cable

This joint effort was reflected in the choice of cable ships: the UK Agamemnon and the US Niagara. The cable had been manufactured in two sections and was too large to be carried by a single ship.

On their first attempt in 1857, the ships left Ireland together, laying one ship’s cable, then splicing, then laying the second ship’s load. This failed when the cable snapped and was lost.

They tried again the following year, this time starting from mid-ocean.

Niagara

The cables were spliced and the ships ran towards the coasts of Ireland and Newfoundland respectively. But they were caught in a ferocious storm and the Agamemnon was nearly lost. They tried again: the cable broke.

By the fourth attempt, the crews were exhausted, they were running low on spare cable and fuel and the Agamemnon had already run out of fresh food. Once more the cable snapped. With just enough fuel remaining for one last try, the two ships attempted another rendezvous but lost each other in the fog and had to return home.

There was enough cable left for one more attempt so the ships were refuelled and provisioned and doggedly set out again. The splice was made and the ships set out for the last time. The Niagara veered off course and had to be steered back, a whale nearly snapped the cable and the Agamemnon just missed a collision with an American schooner en route, but they finally reached Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, and Valentia, Ireland on the 4th and 5th of August 1858 respectively.

Success and failure

The first official message sent along the cable on the 16th of August read, ‘Europe and America are united by telegraphic communication. Glory to God in the highest, on earth peace, goodwill to men.’

The problems of the cable voyages, however, were to continue. Sheer determination had got the cable across the ocean, but there had been faults in its manufacture and it had been damaged by the cable laying machinery. The final blow came when the engineer Wildman Whitehouse insisted on using high voltage instruments which further damaged the cable. It stopped working on 20th October 1858.

Sketch showing towing the cable ashore

Despite despair at this catastrophe, the Atlantic Telegraph Company did not give up the ambition of uniting the two continents. Lessons had been learned, especially on the need for careful cable manufacture and laying, and the cable had worked, despite the massive problems encountered by the engineers and the ships. So the hurried and dangerous voyages of the 1850s laid the foundations of the successful cable of the next decade.

We’re upgrading our systems, and this includes changes to our customer and member account log in, MyIET. It’s part of our big picture plan to deliver a great experience for you and our wider engineering community.

Whilst most of our websites remain available for browsing, it will not be possible to log in to purchase products or access services from Thursday, 17 April to Wednesday, 30 April 2025. Our Member Relations team is here to help and for many of our services, including processing payments or orders, we’ll be able to support you over the phone on +44 (0)1438 765678 or email via membership@theiet.org.

We apologise for any inconvenience this may cause and thank you for your understanding.

For further information related to specific products and services, please visit our FAQs webpage.