As part of the Savoy Place refurbishment, a condition was stipulated that an archaeological investigation was to be undertaken on the site. This was carried out between October 2013 and November 2014 by MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology).

In total seven trenches were dug and examined with the excavation restricted to new pile positions, a new lift pit and a new drainage tank. Several exciting finds were made dating back to the medieval period.

The full report on the results of the excavation is held in the IET Archives but a summary of the fascinating discoveries are described below.

A site of many transformations

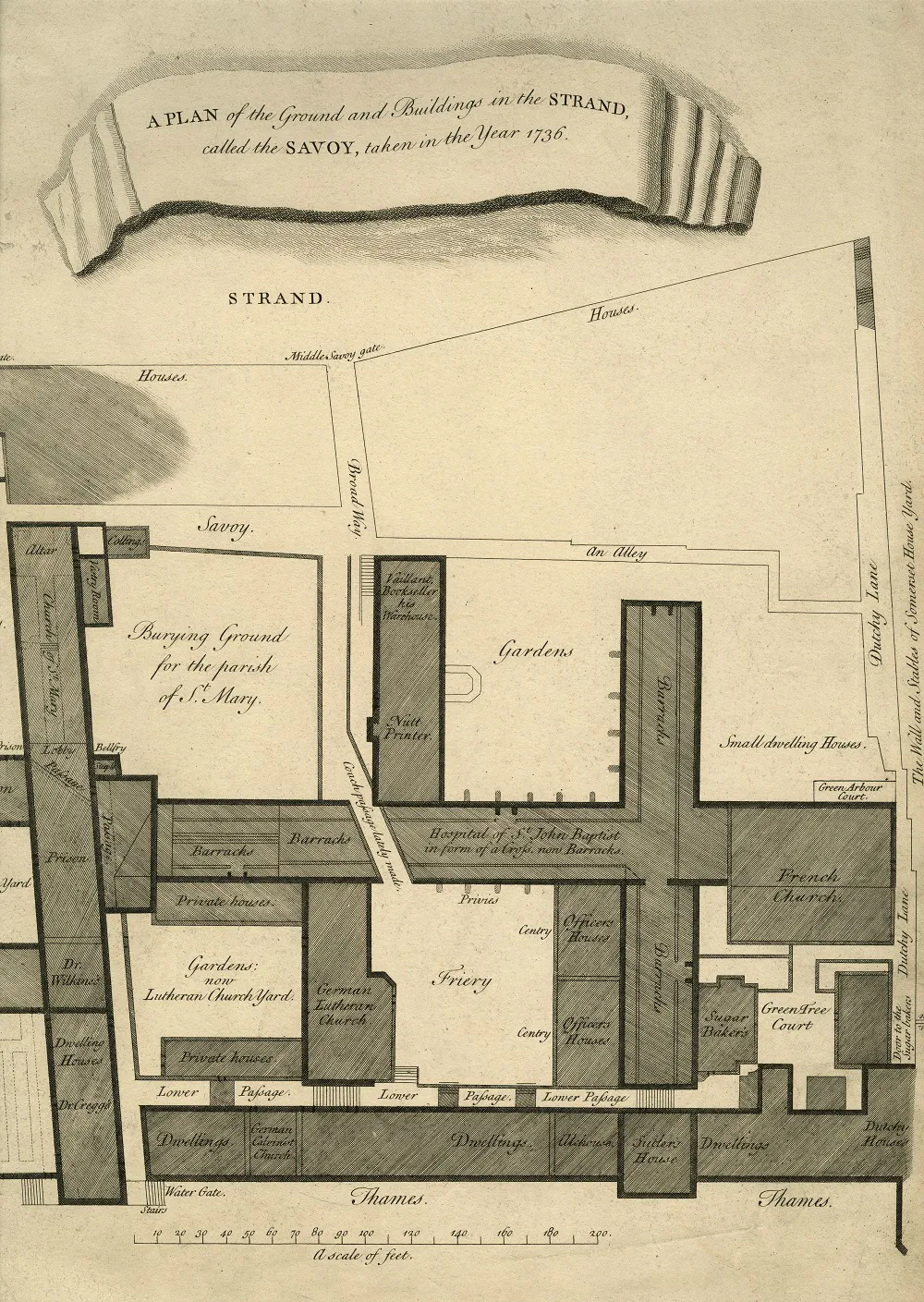

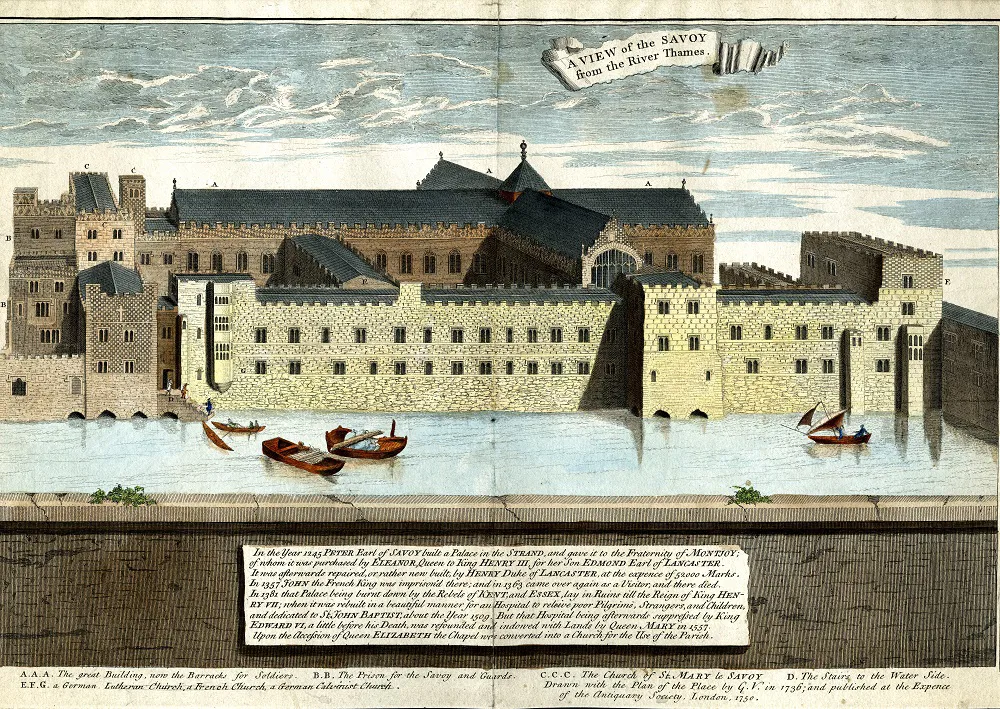

A view of The Savoy from the River Thames 1760

The area of the Savoy Manor takes its name from Peter, Count of Savoy, who was given the land by Henry III on 12 February 1246.

He built a palace on this site but after he died in 1268 the property was left to a hospice in Savoy. However, his niece, Eleanor of Provence, Queen to Henry III, bought back the land.

The land was given to her son, Edmund Plantagenet, the first earl of Lancaster. The original layout of the palace is unknown but was extended by successive Earls of Lancaster. It was partially destroyed during the Peasant’s Revolt of 1381.

Plan of The Savoy 1736

More information about the Savoy Palace and its later conversions can be read in the history of the Savoy and the IET London: Savoy Place.

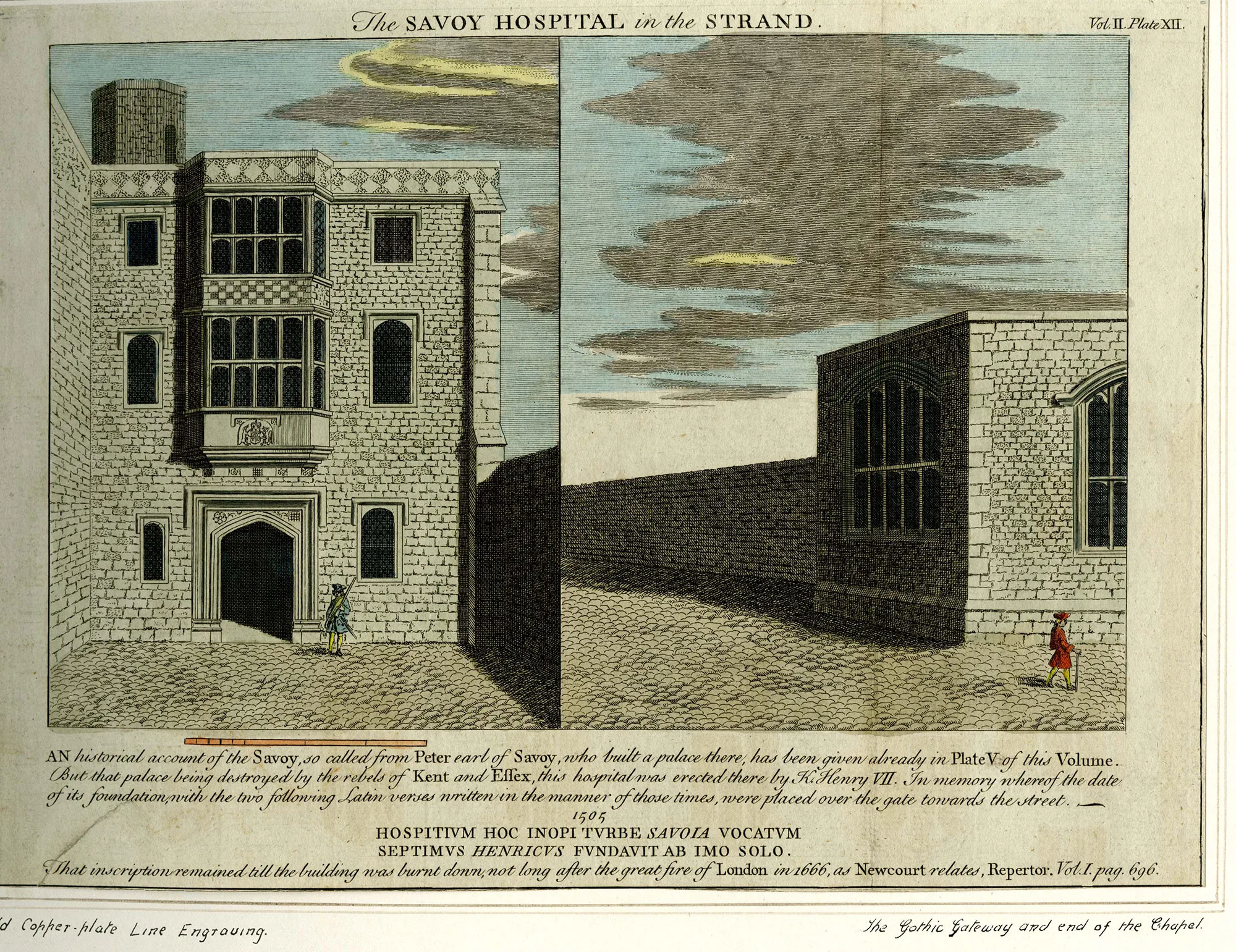

One of the most significant alterations of the Palace was the creation of a hospital in the early 16th century. This large complex was founded by Henry VII in 1508. It was built to provide relief for up to 100 paupers a night with a staff of doctors and nursing sisters. The last poor were admitted in 1642, the hospital then being used as barracks.

Looking at a plan of the vicinity dated 1736 it is possible to see that private houses were present in the southern part of the site.

In the southwestern section, there was a military prison, private dwellings and the river stairs. There were several churches located in different parts of the old hospital buildings (French Church, German Lutheran Church – previously the Sisters’ Hall in the hospital until 1694, and the Church of St Mary).

Waterloo Bridge

The construction of the first Waterloo Bridge between 1811 and 1817 and then the Victoria Embankment between 1864 and 1870 removed all the hospital buildings except for the chapel of St John which still survives.

19th century

The current building was built between 1886 and 1889 to serve as an examination hall for the Royal College of Physicians and the Royal College of Surgeons. This is the building that the current Institution of Engineering and Technology now occupies. More information on the building, its history and recent renovations, can be read in the history of the Savoy and the IET London: Savoy Place.

Uncovering pieces of the past

In addition to the earlier stonework and walls that were discovered in the trenches, there were a number of smaller items that were of particular interest. They range in date and show who occupied the site and when so a picture can be drawn to illustrate the past that has long since disappeared.

Tiles

Large numbers of mid-late 14th century Penn floor tiles (from Penn, Buckinghamshire) were found. The vast majority were decorated but a few yellow and brown glazed examples were also present. Some of the unworn tiles could have been ‘wasters’, those which were discarded without being used. These include a number of tiles with clay accidentally attached to the upper surface during the firing stage.

Another tile found was a Low Countries ‘Flemish’ fragment dating probably from the 14th - late 15th century. The surviving top corner has a round nail hole. There was also a thinner, possibly Tudor, tile that had a plain green glaze above a white slip.

An unworn plain white tin-glazed floor tile was found. It is unusually large measuring 169mm in breadth. Plain glazed tin-glazed floor tiles are relatively uncommon in London, the majority are decorated. This is probably mid-16th to mid-17th century.

Although some medieval pottery was recovered during the archaeological excavations, no structural remains could be identified as part of the original Savoy Palace.

The ceramic building material possibly provides the first evidence of the types of flooring installed in the Savoy Palace. It is possible that Penn tiles were laid when the palace occupied by John of Gaunt after 1362. The surviving tiles suggest the floors comprised strips of decorated examples separated by thin rows of plain glazed tiles.

It is not known if the hospital (founded in 1508) reused pre-existing buildings from the Savoy Palace, as there are no known plans of the Palace. The amount of medieval pottery and Penn floor tiles recovered does suggest some of the Savoy Palace had survived and had been reused.

The Low Countries floor tiles were probably installed in the hospital in the early 16th century. They were most likely laid in a chequerboard pattern with plain yellow glaze tiles alternating with green/brown tiles.

As there are no known images of the interior of the Savoy Palace or the hospital the discovery of these tile fragments help us to understand what it could have been like all those years ago.

The Hospital at The Savoy

Pottery

Some 24 sherds from 20 vessels were found. The condition of the sherds was poor but because they were found in isolation they are of value providing a date range of 13th-14th century land use.

432 sherds recovered in other areas of the excavation date from the post-medieval period (1480-1900). They are characterised by the factory made wares of the Midlands and north England, such as creamware and blue transfer-printed pearlwares. Later examples include 17th century dated Surrey-Hampshire border wares and London made delftware.

A large collection of pottery is London-area redware with a selection of one or two-handled flared bowls, deep bowls and rounded dishes, decorated in a variety of Chinoiserie and foliate designs.

A small number of vessels used for taking hot drinks consist of imported blue and white Chinese porcelain teabowls and handled cups; other drinking vessels include white salt-glazed stoneware tankards with London made stoneware gorges and tankards.

View of The Savoy on the River Thames 1736

Clay tobacco pipes

28 pipe bowls and two stem fragments were uncovered on the site. They were all of typical London manufacture and most had been smoked. They range in date from c1700 to the 1770s but four pipe bowls dated between c1660-1710. Four of the 18th-century examples have a maker’s mark, with at least four different pipe makers represented. Three of these are decorated – a thistle, the Prince of Wales Feathers and the Act of the Union.

Iron

A horseshoe from the 13th or 14th century was discovered. Its defining characteristics are its size and the number and shape of rectangular nail-holes.

Ceramic

Four large ceramic crucible flat base and body pieces were found with deposits of copper-alloy waste. Although difficult to date the flat base suggests an 18th or early 19th-century date.

Two white pipeclay 18th century wig-curlers were also found, one with a stamped makers’ initial on one end.

Out of the items found one can build up a picture of the inhabitants in the area. Although they were casually discarded over time their discovery means we can imagine an area busy with people going about their daily lives eating, drinking, working and entertaining.

Walls and stonework

Lying south of the main river wall a stone wall was discovered with an arch that was 2.40m wide. The arch was built on thick timber baulks partially dug in into the foreshore. A view of the river and the Savoy shows a section of a river wall with arched openings.

The arched wall found in front of the main river wall is part of the Watergate stairs. The arch would have originally supported stairs down to the river. Today the river wall lies 75 metres away from the River Thames, but prior to the construction of the Victorian Embankment, the river would have been wider, extending right up to the water gate of Savoy Place.

It has local and regional significance. Such a large, well-built example of stone river frontage dating from the early 16th century was previously unknown in this area of Westminster.

Understanding our past

The recent refurbishment of Savoy Place allowed for a fascinating insight in to the history of the site afforded by the archaeological excavation by MOLA.

Now we have a greater understanding of how the site has transformed over the centuries. It has witnessed the rise and fall of a great palace. The building has been re-purposed as a hospital, military barracks and a prison. The site has been reclaimed and extended by successive Earls of Lancaster. Private houses and churches have been built and demolished to make way for Victorian public works and regeneration. Archaeological finds have helped us to interpret how these buildings were decorated and used. The different types of pottery unearthed are signs of trade and movement amongst people. This area has been a busy centre being so well positioned by the River Thames and to find evidence of real people living and working here is a fascinating insight into their daily lives and enriches our understanding of this historically significant site.

You can find out more about the building now occupied by the IET by reading a history of the Savoy and the IET London: Savoy Place.

This information has been taken from the MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology) post-excavation assessment and updated project design report in July 2015. A copy of the full report is available, please contact the IET Archives for more information.

We’re upgrading our systems, and this includes changes to our customer and member account log in, MyIET. It’s part of our big picture plan to deliver a great experience for you and our wider engineering community.

Whilst most of our websites remain available for browsing, it will not be possible to log in to purchase products or access services from Thursday, 17 April to Wednesday, 30 April 2025. Our Member Relations team is here to help and for many of our services, including processing payments or orders, we’ll be able to support you over the phone on +44 (0)1438 765678 or email via membership@theiet.org.

We apologise for any inconvenience this may cause and thank you for your understanding.

For further information related to specific products and services, please visit our FAQs webpage.